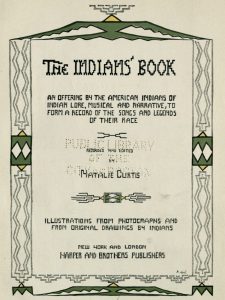

Natalie Curtis Burlin, a white ethnomusicologist and composer from New York, and Angel De Cora, a Winnebago artist from Nebraska, were two educated women who lived at the same time period and had a shared interest in the lives of Native Americans. Curtis Burlin was interested in preserving the music of different tribes as it existed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. De Cora was interested in depicting Native Americans as a people whose outward appearance changed as they gradually became assimilated into white culture. In 1907, Curtis Burlin's book, The Indians' Book, which included many illustrations and lettering by De Cora, was published.

Natalie Curtis Burlin

Natalie Curtis Burlin (April 26, 1875 – October 23, 1921) was born in New York City into a well-to-do family. She was trained as a pianist from a young age at a time when it was very common for young women in the middle and upper classes to take up the piano as a way to add to their social standing. Curtis Burlin's interest in the instrument went far beyond that, and she practiced for hours a day, intent on a career as a musician. Her musical instruction included learning how to compose, and like other women composers of the time she wrote light songs meant to be sung by amateur women in private settings.

A visit to the American Southwest in 1900 changed her life and made her aware of the music of Native Americans. This fully captured her interest, and led her to writing about the music and recording it for posterity. She first found herself in that region when she followed her younger brother George there. He had been sent there in his 20s and was suffering from poor health. His family had hoped that the climate in the Southwest would be beneficial to him. He fell in love with the place, and his enthusiasm led Curtis Burlin to accept the invitation to visit him in Arizona. It was during this visit that she first heard a Native American song and immediately threw herself into visiting more reservations in the wider region to hear more music. She then wrote about her experiences for publication in magazines for the general reader. She transcribed several songs for individual publication, and eventually wrote the book for which she is best known, The Indians' Book, published in 1907.

By 1910, Curtis Burlin broadened her interest to that of the music of Black Americans — the Spirituals and folksongs that they sang at the time. She had been exposed to their music when working at the Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, a college that was started to educated Black people who had been freed from slavery. The college at the time also educated Native American people, and Angel De Cora was one such person who spent some time there. She transcribed what she heard into several books, and her work was funded by the philanthropist George Foster Peabody.

Curtis Burlin then went on to join David Mannes in the founding of the Music School Settlement for Colored People in New York in 1911. In 1912, she helped to sponsor the first concert at Carnegie Hall that featured black musicians. She married Paul Burlin, an artist, in 1917. Her last book was published in 1920, Songs and Tales from the Dark Continent, where she took the same approach to Africans as she had done to Native Americans. Unlike the work she did on site for The Indians' Book and the four volume The Hampton Series of Negro Folk Songs, that last work was only based upon the work she did with two African students who were enrolled at the Hampton Institute rather than with a larger number of people. She died in a car accident in 1921 when living in Paris.

Angel De Cora

Angel De Cora Dietz (1871–1919), also known by her Ho-Chunk name, Henook-Makhewe-Kelenaka (Fleecy Cloud Floating in Place) was born and raised on a Nebraska Winnebago reservation. Like other Native children at that time, she was educated far from home at a boarding school for Native children when she was 14 years old in 1883. In her case, she was abducted and sent to Virginia to the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute. This school was established in 1868 for freed Black enslaved people, and the so-called Indian Department was created in 1878. Students were expected to be taught to be fully assimilated Americans who would then bring back their new ways to be good examples at home. Like other students she was homesick, and it was the art class that gave her heart ease. The art class was a new addition to the education of students at the school, having started as an experiment the summer before she arrived there.

She traveled with the other Native students to the Berkshires during the summer of 1886. Students were placed with local families in order to further foster mainstream American cultural assimilation. They returned to Virginia in the fall. For girls, the school schedule emphasized a domestic education with the purpose of training the girls to be wives and mothers back home. De Cora returned to Nebraska in 1887 because Indian Affairs required boarding school students to be returned home after three to four years. She stayed on the reservation through the fall of 1888 and then returned to the Institute as a Junior student. Her senior year was the 1890-91 academic year. After she graduated, she was able to attend a Miss Mary Burnham's Preparatory School for Girls, a women's preparatory school in Northampton, MA, as a scholarship student in music. She did not enjoy her time there, and soon wished to attend Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies where she'd be able to study art seriously. That plan never materialized, but instead she was enrolled in the four year course at the School of Art at Smith College. As an art student, she wouldn't have to take normal college courses, but neither would she receive a college degree there. She then transferred to the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia for two years, and then was briefly at the Cowles Art School before landing at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School for two years. When her academic time was done, she first set up a studio in Boston then later moved it to New York City. In New York, she would do illustrative work for several of the publishing houses there.

From 1906 to 1915, she was the director of the Leupp Art Department at the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. At that time, Native Americans were considered to be good inspiration for art, but not creators of art themselves. The program she developed there was intensive, for she believed that the students had a special talent for art and would contribute to contemporary American art in a lasting way. While at Carlisle she met another Native artist, William Dietz, and the two married in 1908. They divorced in 1918, and she moved back to New York City to continue her work as an illustrator.

Besides her work as an artist, she lectured widely on both Native affairs and Native art and authored several articles. She died in New York City on February 6, 1919, and is buried in an unmarked grave at the Bridge Street Cemetery in Northampton, Massachusetts.

The Indians' Book

When Curtis Burlin started to write this book, it was illegal for Native Americans to perform their own songs in the government schools. She was warned that if she wanted to record the music of these people, she would have to do so in secret because if someone from the government were to hear of it she would be banished from the reservation. At some reservations, the people were afraid to sing their songs for fear of getting into trouble with government officials. She appealed to President Theodore Roosevelt, asking that it be made possible for her to record the songs openly. He not only agreed to this, but became personally interested in the project and helped to bring about a positive change in the administration of government of Native affairs. This meant that songs that had once been forbidden in the so-called Indian Schools were now not only permitted but encouraged. Children at these schools were now allowed to embrace their cultures and spirituality, things that had previously been denied to them there.

De Cora was appointed as the art instructor at one of the government schools which had previously not employed Native teachers of any subject.

A note in the preface shows that Curtis Burlin considered this book to be an accurate recording of the songs, stories, and artwork of Native people:

The Indians are the authors of this volume. The songs and stories are theirs; the drawings, cover-design, and title-pages were made by them.

The work of the recorder has been but the collecting, editing, and arranging of the Indians' contributions.

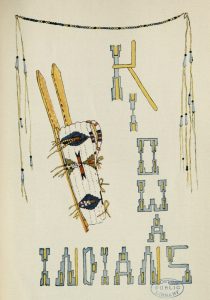

Angel De Cora's work is spread throughout the book. She was the book's designer of the cover art, which depicts a parfleche (a type of bag made out of rawhide used by people of the Prairie tribes to hold and carry objects like dried buffalo meat) that was painted by the Cheyenne woman Wihunahe. The title page, also designed by De Cora, features an adaptation of the Eagle (seen at the top of the page with outspread green wings and a yellow beak) and the Eagle's Song (the framing decorations). The eagle was chosen because of its strength.

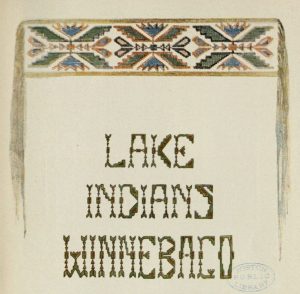

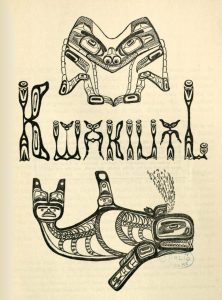

Songs and stories along with some artwork and photographs of groups representing major geographic regions of Native Americans are represented in this book: Eastern (Wabanaki), Plains (Dakota, Pawnee, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa), Lake (Winnebago), Northwest (Kwakiutl), Southwestern (Pima, Apache, Mojave-Apache, Yuma, Navajo), and Pueblo (Zuni, San Juan, Acoma, Laguna, Hopi).

This is not a full representation of Native American groups throughout this country, and the names as they are now known will sometimes differ from how they are referred to in this text.

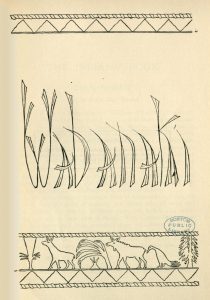

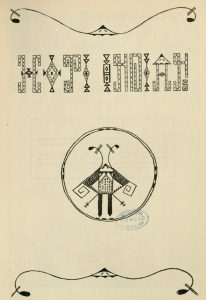

Each tribe is given its own chapter that includes a title page with lettering designed by De Cora that is meant to reflect the visual style of the tribe. To the right are some examples of the title pages.

Curtis Burlin's purpose in making this book was to record the songs and stories of Native peoples in hope that it would help transmit their traditions back to the younger generation, who at the time were being prevented from learning those ways because of the interference of the U.S. Government.

She started the work in 1903, and at first she used a phonograph to record the songs but soon abandoned it in favor of the simple notebook and pencil. The singers were the ones who choose which songs would be included in this volume, and Curtis Burlin knew that there would be some songs deliberately not sung because of their relation to certain occasions or ceremonies.

It was her hope that this book would serve to encourage college-educated Native people to continue this work of recording stories and songs of their people on their own. The singers were "old men and young, mothers and maidens" in order to try and capture a fuller part of the lives of these people.

The poetry of the songs has been included in a transcription of the original language and then translated into English, which had been done using educated Native people as translators and the old men as authorities of the words.

Because of the symbolic nature of some of the language, direct translations were challenging.

The book was published in 1907 and remains in print and is a valuable piece of scholarship to this day. Her attitudes were largely progressive for her time period, but modern readers will note that the explanatory text sometimes does use language that refer to Native peoples as "primitive" and relies on old "noble savage" stereotypes.

Curtis Burlin also shared the belief of the time that the Native people were dying out as a race because of their becoming so-called "civilized," rather than growing and changing with time. It is for that reason that modern readers should be cautioned when using this book to explore this rich heritage of story and song.

Examples of Songs

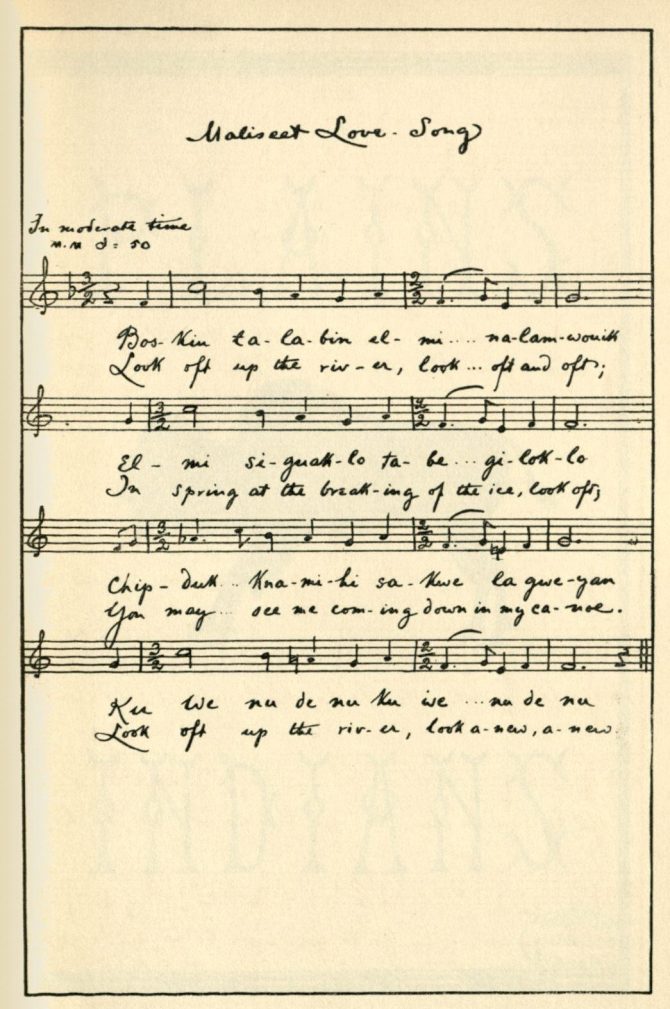

Maliseet Love-Song

This song comes from St. John, New Brunswick. It is a hunter's farewell song. In the autumn, the youth sets out for the long winter hunt, and parts from his love, telling her to watch for him at the breaking of the ice in the spring, that she may see him coming down the river in his canoe.

The Wabanakis have many such songs. They call them "Songs of Loneliness."

| Bosku ta-la bin | Look oft up the river, look oft and oft, |

| Elmi na-lamwoulk | In spring at the breaking of the ice, |

| Elmi siguak-lo |

look oft; |

| Tabagi-lok-lo | You may see me coming down in my |

| Chipduk knamihi |

canoe. |

| Sakwelagweyan | Look oft up the river, look anew, anew. |

|

Ku we nu de nu Ku we nu de nu |

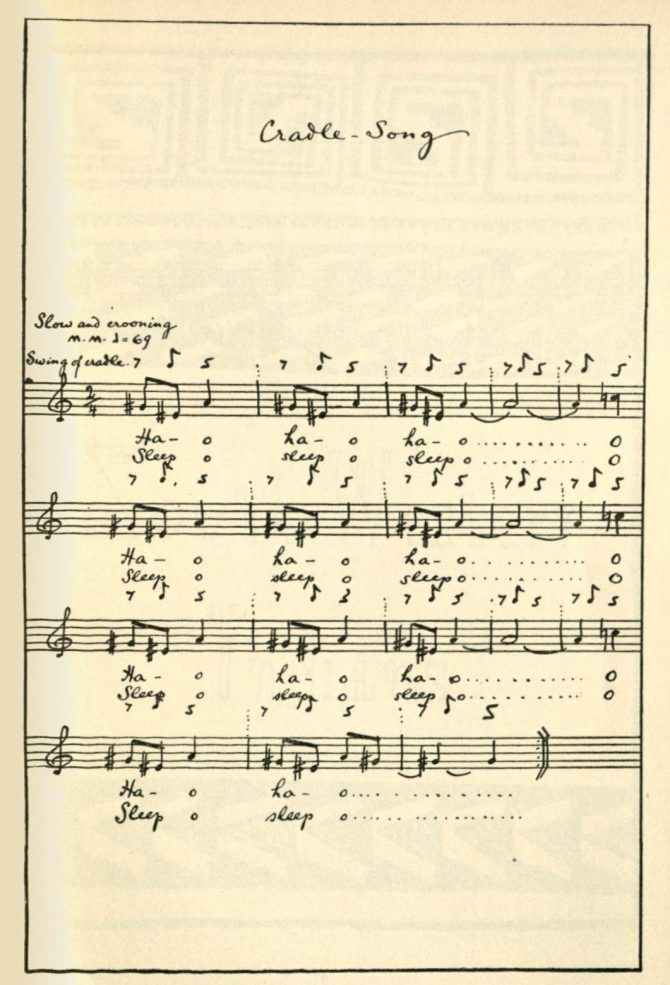

Kwakiutl Cradle-Song

The Kwakiutl baby hangs in his cradle from a cross-beam in a corner of the house. A cord is attached to the cradle, and the mother rocks her baby by pulling on the cord. To and fro swings the cradle, to and fro, while the mother sings a lullaby.

Sometimes the cradle is hung from a long pole, the end of which is fixed aslant in the ground while the middle rests on a forked stick set upright in the earth. The cradle hangs from the free, flexible end of the pole, and instead of swinging to and fro, it springs up and down with the mother's touch upon the cord — up and down, up and down, while the mother sings a lullaby.

| Ha-o Ha-o Ha-o | Sleep o sleep o sleep o |

Books

The Healing of Natalie Curtis [fiction]

Angel De Cora, Karen Thronson, and the Art of Place

Add a comment to: Natalie Curtis Burlin and Angel De Cora