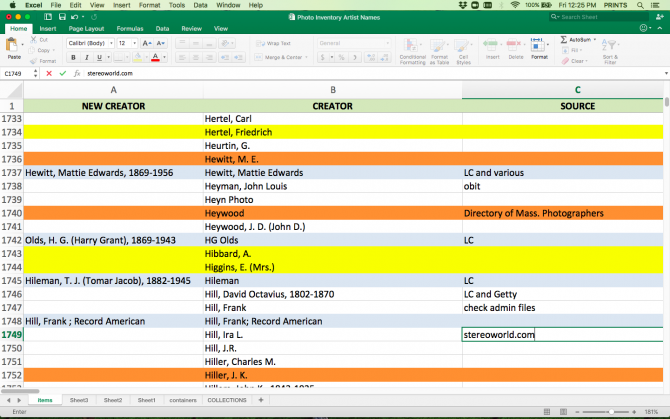

Working with the Boston Public Library’s extensive photographic collections from home has been a challenge. While digitized images are crucial in our work, evaluating an object that you cannot see in person is like solving a murder with just the chalk outline. But thanks to a photograph inventory project at the BPL completed in 2019, we can use recorded data to learn about the history and context of the images. In the last four months, we have concentrated our efforts on learning more about the personal histories of the photographers represented in our collection.

In this period, we have made a particular effort to learn more about the collection's women photographers. In doing so, we were able to discover the stories of some of the pioneers in their field.

In 19th century commercial photography, it is well documented that many of those working in photographic studios were women. They worked as greeters to the customers, and behind the scene as colorists. (This was considered an appropriately “feminine” professional pursuit at the time.) Some women did the technical work of printing and developing the images, but they almost never had their name stamped on the photograph, denying them due credit.

But through our demographic research, we have discovered a number of photographs taken by women who founded and ran commercial studios. These include:

- Emilie Bieber, who was likely the first woman to run a photo studio in Germany

- Adèle Perlmutter-Heilperin of Atelier Adèle in Vienna, who ran a studio co-owned with her brothers and was the only woman to be appointed a photographer of the Austrian imperial court

- The mysterious Madame del Tufo, who ran a studio in Colombo, Sri Lanka

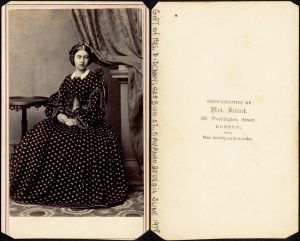

Closer to home in Boston, we have the fascinating story of Helen F. Stuart, who started her career as a “hair artist” and taught herself photography to document her creations. She expanded her interest in the photographic arts and became involved in Spirit Photography, a macabre fad that used photographic trickery to create images that depicted departed loved ones floating as spirits in the background. While we don’t have any examples of her spirit work in our collection, Stuart’s earth-bound portraits prove her talent.

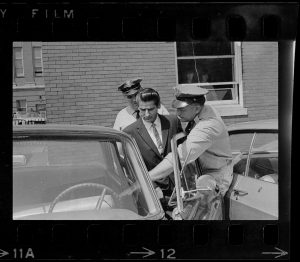

Thanks to the Associates of the Boston Public Library, the work of many press photographers is discoverable online in the Brearley Collection, a huge aid to those of us working with these collections from home. As we see from our press holdings, opportunities for women photographers in the commercial realm became more plentiful in the last half of the 20th century. While working as a press photographer was a high pressure, low pay, and largely anonymous pursuit, it put you on the front row of history as it was being made.

Two of the most well represented female photographers in our collection include Judith Buck and Teresa Zabala, who made their living in this rough and tumble world of newspaper photography: Buck for the Boston Herald as early as 1965, and Zabala first for the Boston Record-American and later for a long stint at the New York Times. We are just starting to uncover their stories and look forward to sharing this research with the public alongside their groundbreaking work.

Add a comment to: When You Can’t Look at the Photograph, Look Into the Person Behind It