A Martial Legacy

"The word was probably spread with the reintroduction of rats to Northern Europe during the Viking Age..."

From the Oxford English Dictionary entry for 'rat'

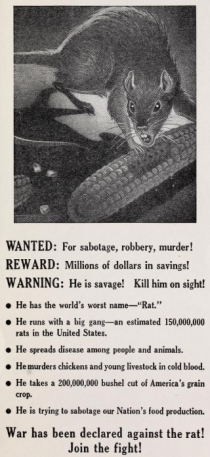

From the moment it set foot on American soil, the brown or Norway rat has always been linked with war. It is claimed that Hessian mercenaries working for the British during the Revolutionary War brought the first brown rats to the British colonies in grain crates. 1 This introduction, though accidental, must rank among the great acts of biological warfare in human history. For long after the British and their mercenaries departed, the rats remain, like a murine fifth column still struggling for mastery of the continent. Or so we have been led to believe.

Ever since that first deployment, the language of war has followed Rattus norvegicus wherever it has naively sought its own slice of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. In his social history of Rats in New York, Robert Sullivan notes that "rats stories are war stories, and they are told in conversation and on the news, in dispatches from the front that is all around us, though mostly underneath." 2

Boston has been no exception to this trend. It has become so normal to describe the relationship between humans and rats as one of "an unending and brutish war" that we may not give it a moment’s thought. But as we shall see, there may be important ways in which the militarism of this language has had a questionable influence on the way we think about and relate to the most abundant mammal species that shares our home.

The People’s Struggle

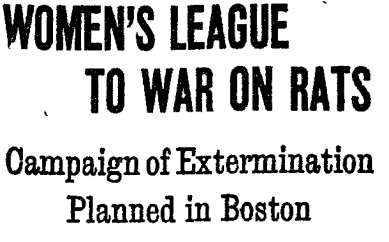

In the early twentieth century there were no city ordinances or state laws regarding the brown rat, so in true democratic spirit one of the early wars was begun from below. It was a civic uprising led by the Women’s Municipal League of Boston. As in so many U.S. wars, humanitarian and economic motives marched side by side. Rats were already seen as a threat to public health and as potential carriers of plague. But in 1908 the Boston Globe also claimed that Boston’s “destructive rat army” caused $10,000,000 in damages each year. When a “formal declaration of war was served on the rat colony of Boston,” in November 1916, the League made sure to call for “the cooperation and support of the business interests of the city.” 3

Government and business interests joined the cause, and a cash bounty was offered for enemy corpses. But in March 1917 the Globe reported that “a cold snap” and “general apathy” had undermined the success of the Women’s Municipal League’s war on rats. A harsh winter and poor morale had ruined Napoleon’s Russian campaign, and now history seemed to be repeating itself. 4 It would prove to be a dispiriting precedent. Time after time offensives were initiated with much bluster and verve, only to fizzle out later amidst finger pointing and muted admissions of defeat.

The Battle for Back Bay

Nowhere was this cycle of disappointment more clear than in the rodent control campaign waged in the Back Bay in 1961. The Globe called it “doomsday” for the neighborhood’s rats and praised the campaign’s “annihilation plans.” They even reported (apparently with a straight face) that “total extermination is the goal.” 5

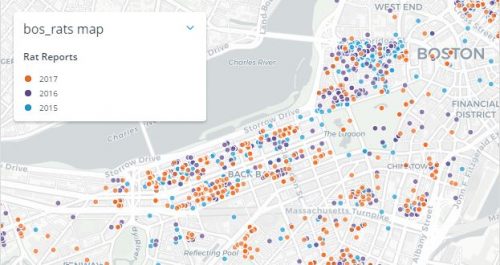

The next month morale remained high; the word “winning” was bandied about, and the Globe asserted “on the best of authority that rats are dying like flies in the Back Bay.” 6 But however the rats may have been dying, they were apparently (and unfortunately for the humans involved) not dying like rats, for by February 1962 the paper announced the failure of this latest war of annihilation, casting blame (yet again) on an uncooperative citizenry. 7 A recent map of rat sightings shows how the war effort has played out over the long term:

Despite this pattern of failure, anti-rat operations continued throughout the century. Low intensity conflicts and guerrilla operations alternated with large-scale war efforts and mass mobilizations.

Sometimes the theater of operations was small, as in 1938, when City Hall reporters “vowed no quarter” against the rats that consumed the potted shamrock in their press room. 8 At other times, huge swathes of Boston were drawn into the conflict, as in the five-front “City Rat War” waged in 1966 in the Back Bay (yet again), the South End, Roxbury, North Dorchester, and the Blue Hill Ave. and Talbot Ave. section of Dorchester. 9

Join us next time as we follow the course of this great struggle up to the present.

References

- Whitaker, John O., Jr. National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mammals. Knopf, 1996.

- Sullivan, Robert. Rats: Observations on the History and Habitat of the City’s Most Unwanted Inhabitants. Bloomsbury, 2004. Both quotations from p. 34.

- “Millions for Rats.” Boston Globe, 24 May. 1908, p. 44. ; “Women’s League to War on Rats.” Boston Globe, 23 Nov. 1916, p.18.

- “Rats Cost $1.34 Apiece.” Boston Globe, 18 Mar. 1917, p. 53. For a recent appraisal of the Women's Municipal League's rat war, see Cavanaugh, Ray. "Dead rodents, but a livelier civic spirit." Boston Globe, 12 Feb. 2017, p. K2.

- Walsh, Patricia. “Back Bay Rats Face Doomsday by Dec. 1.” Boston Globe, 29 Oct. 1961, p. 14.

- Walsh, Patrick. “Back Bay Winning In War on Rats.” Boston Globe, 18 Nov. 1961, p. C36.

- Walsh, Patricia. “Back Bay Rat Menace Remains, Many Residents Fail to Help.” Boston Globe, 9 Feb. 1962, p. 28.

- “City Hall Reporters War on Rats That Ate Press Room Shamrocks.” Boston Globe, 30 Mar. 1938, p. 5.

- Friedman, Elliot. “5 Areas Targets in City Rat War.” Boston Globe, 30 Jun. 1966, p. 20.

Add a comment to: A Military History of the Brown Rat in Boston, Part I