Introduction

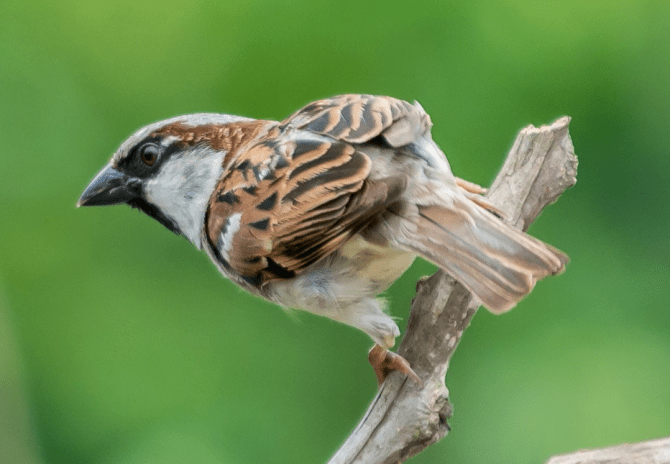

There’s little chance you haven’t seen house sparrows, though you may not have paid them much attention. These little brown birds can be found just about everywhere in Boston (and in the entire urban world): perched outside apartment buildings, gleaning crumbs from café tables, and even fluttering and hopping around the courtyard at the BPL’s Central Library. They’re so ubiquitous that it’s easy to forget that they’re actually quite recent additions to the fauna of the city.

As an entry into the history of these little birds in Boston, let’s turn to Horace Winslow Wright’s 1909 Birds of the Boston Public Garden, a BPL copy of which has been digitized and may be read on the Internet Archive:

The House, or English, Sparrow was successfully introduced into Boston by provision of the city government in the year 1869 after an unsuccessful effort made in the preceding year. From that time dates its occupancy of the Common and the Public Garden and its spread throughout the city and thence to suburban cities and towns and thus more and more widely.

So the coming of house sparrows to Boston was not some haphazard release, but a deliberate introduction at the behest of the City itself. But their coming was not without controversy: from before their arrival through the decades afterwards, house sparrows were a source of contention, and as is the case with rats, metaphor has played a major role in how these birds were discussed and represented.

1867-1868: The Pre-Sparrow Debate

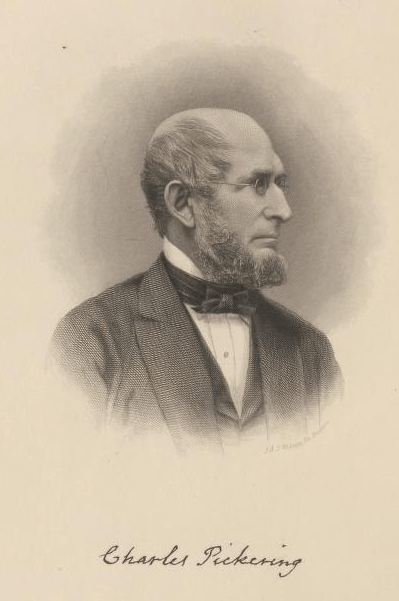

On April 17, 1867, doctor, naturalist, and “race scientist” Charles Pickering stood before a meeting of the Boston Society of Natural History to decry the “great evil” portended by the recent introduction of the house sparrow elsewhere in the country, calling it the “acknowledged enemy of mankind for more than five thousand years.” He warned that these “impudent parasites” stole human food and that their supposed benefits for insect control were far outweighed by their pernicious grain thievery. He even cited English poetry as proof that the birds’ “destructive propensities” were well known in that country.

(Read the full account of Pickering’s talk in the Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History, vol. 11. on HathiTrust)

In the May 1868 issue of the Atlantic Monthly (also available on HathiTrust), Boston ornithologist Thomas Mayo Brewer made a direct reply to Pickering (though without calling him by name). Brewer came to the sparrows’ defense, arguing that they do “a great deal of good” and arguing in favor of their introduction to control insects. Citing English and French sources, Brewer pointed out the deleterious effects presumably caused by efforts to extirpate the sparrows in Europe, and cited the beneficial role they had played in protecting New York shade trees from caterpillars since their introduction there.

Near the end of his article, Brewer includes a sentence important for our purposes: “The committee on public squares of the city government of Boston have just made arrangements to introduce them into the Public Garden and the Common.”

Brewer ends on an optimistic note, claiming that “we cannot doubt that the house-sparrow will erelong become one of our most common and familiar favorites.” Common and familiar it indeed became, but as we shall see, for many people it was far from a favorite.

Join us next time as the sparrows are introduced and learn how they fared in their early years in Boston.

Further Reading

Read a biography of Charles Pickering in the 1920 American Medical Biographies.

Read an 1880 obituary of Thomas Mayo Brewer in the Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club available through JSTOR.

Add a comment to: The House Sparrow in Boston, Part I