Boston abolitionists faced great opposition from their fellow Northerners during the early years of the anti-slavery movement. To say that everyone in the North supported an end to slavery would not have been true. Many letters, which you can help transcribe online at the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts Project, discuss how pro-slavery mobs often interrupted abolitionist meetings.

The most violent of these incidents happened on October 21, 1835, at the offices of The Liberator, a newspaper edited by the white abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison. The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society held a meeting there, and Garrison volunteered to give a speech. Newspapers misreported that a fiery British abolitionist, George Thompson, would speak at the event. This angered local, wealthy Bostonians, who owned businesses in the textile industry. They did not support abolition because they profited from the cheap cotton produced by slave labor in the South. Led by the Mayor of Boston, a crowd of men gathered outside the offices with violent intentions. Garrison recalled in an account that as the meeting began, members could hear “the howlings of the riotous throng” outside. One female member wrote for the October 24th issue of The Liberator, describing the mob of men sarcastically as “gentlemen of wealth and standing” in Boston. These “gentlemen” surrounded the building, forced the women outside, and seized Garrison. They then marched him through the streets with a rope tied around his waist. The mob nearly tarred and feathered Garrison, but the Mayor interfered to prevent any further violence.

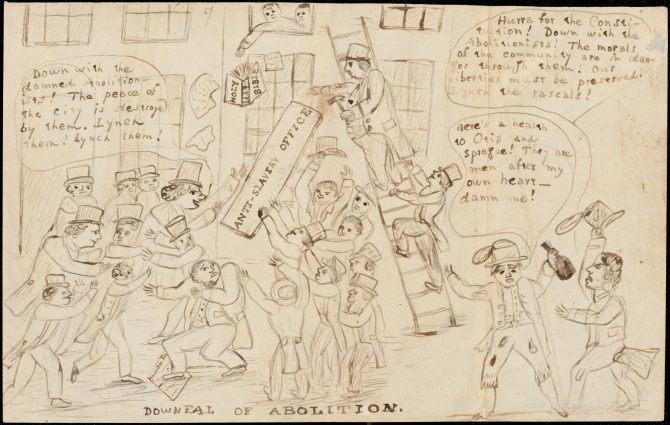

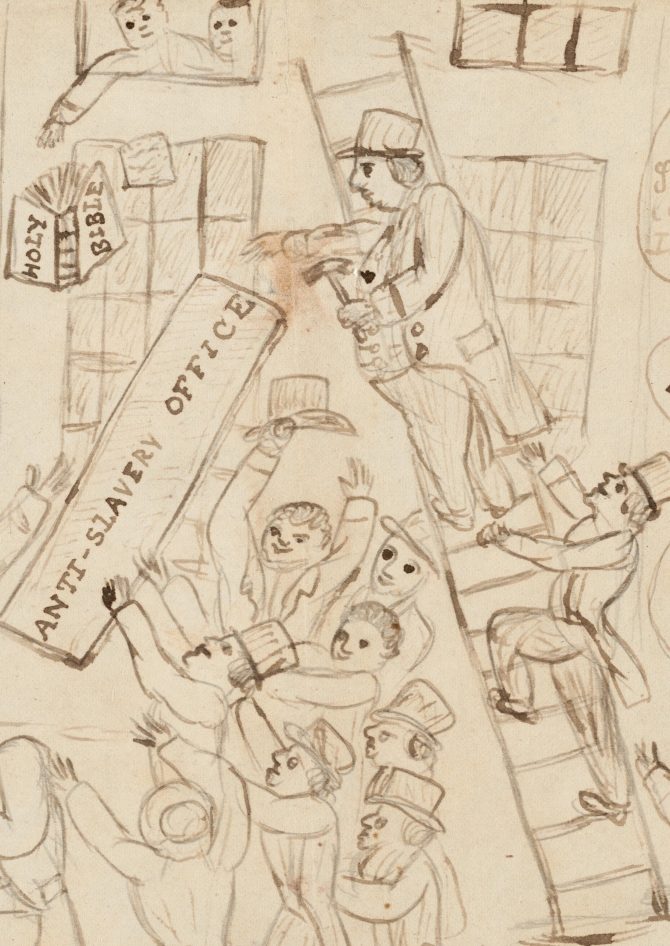

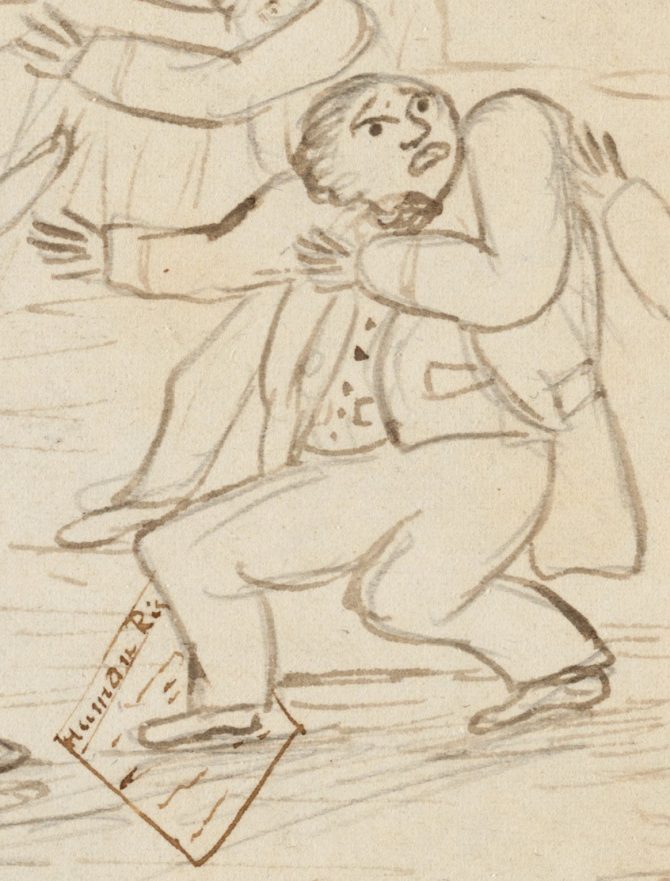

A cartoon, possibly from 1835, depicts the violence from that day. Wealthy men in top hats create chaos as they tear down a sign from the Anti-Slavery office. Men inside the building dump papers outside the window, including a copy of the Bible. This suggests that their actions did not align with Christian values. Garrison remembered this particular episode with horror: “The rioters...got hold of some prayer and hymn books, belonging to a religious society that occupied the hall every Sunday, and threw them out of the window as incendiary documents!”

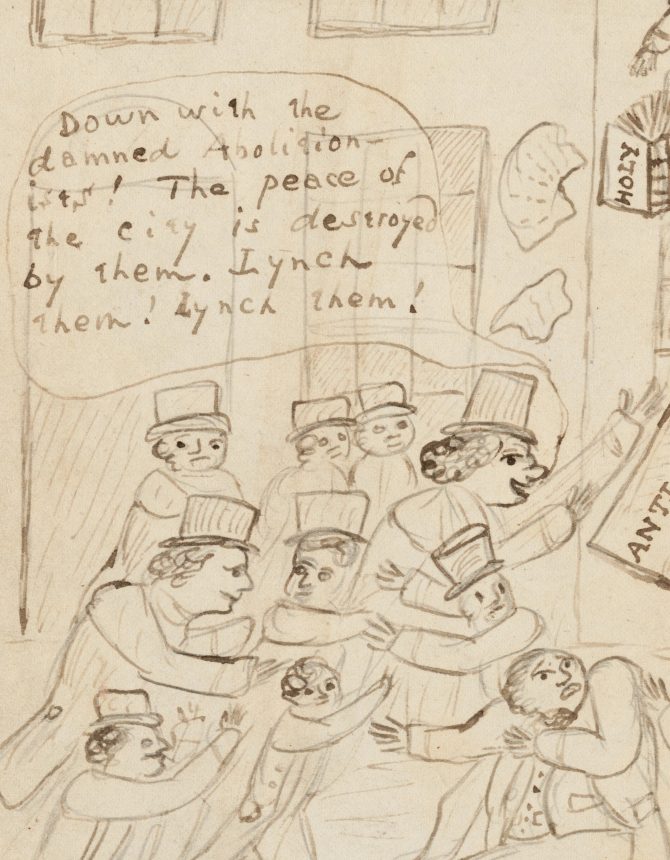

In the cartoon, one of the rioters yells, “Down with the damned Abolitionists! The peace of the city is destroyed by them. Lynch them! Lynch them!” The anonymous cartoonist subtly implies that it is in fact the pro-slavery mob with its violent actions that has destroyed the peace of the city and not the abolitionists.

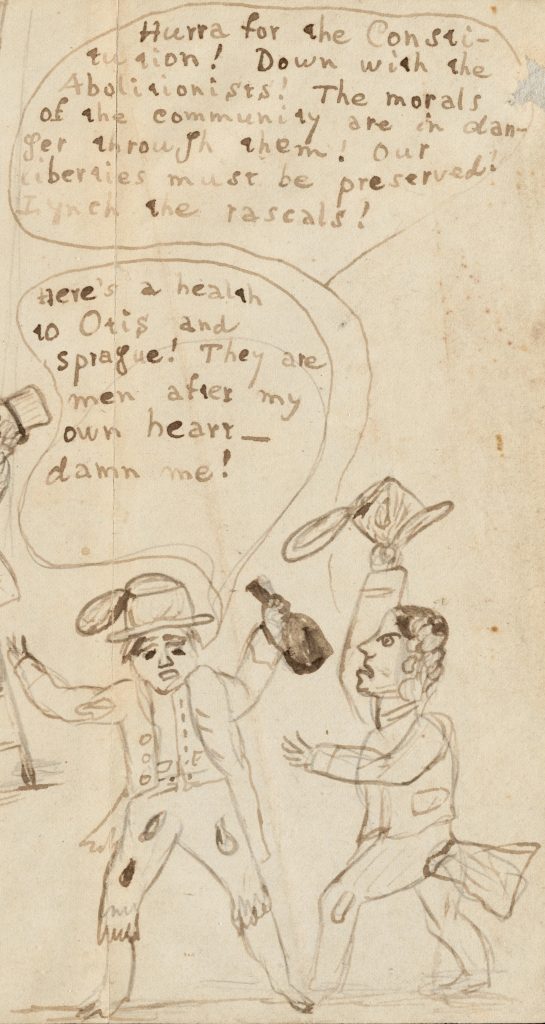

Two drunk and disheveled men on the right appear to praise the mob. The artist highlights their disrespectful appearance to suggest that they are not respectful members of society and should not be taken seriously. The man on the left praises two local politicians, Harrison Gray Otis and Peleg Sprague, who supported the anti-abolitionists. The other man declares, “Hurra for the Constitution! Down with the Abolitionists! The morals of the community are in danger through them! Our Liberties must be preserved! Lynch the rascals!” Details from the cartoon, however, suggest that this pro-slavery mob does not respect the Constitution. One Bostonian steps on a piece of paper that reads, “Human Rights,” clearly not respecting the abolitionists’ right to free speech and peaceful assembly.

Abolitionists received many threats from other Northerners. Garrison wrote that “every mail brought letters to [him], declaring that [he] had only so many days to live.” He also “received representations on sheets of paper, showing [him] up as tarred and feathered, or hung by the neck, or stabbed to the heart, because of [his] sympathy for the oppressed.” Black and white abolitionists bravely spoke out, knowing they might be attacked because of their beliefs. In 1835, a community of free blacks in Philadelphia were driven from their homes by a pro-slavery mob. Threatened with violence, abolitionists boldly fought for the emancipation of slaves until their words and actions began to turn Northern hearts.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Add a comment to: The Boston Mob of 1835