How do you research a neighborhood’s history? And how do you conduct this research when the records you need are in many places at once? We’re working to simplify this process for community researchers investigating Chinatown's history. The BPL has teamed up with the Boston Research Center, Northeastern University Library, and neighborhood organizations. Together, we are inventorying Chinatown's historical collections. Read on to find out how we're gathering community feedback to locate historical collections around Greater Boston, and how we can use these materials to learn more about Chinatown's history.

First, Some History

Boston’s Chinatown rests upon manmade land, created by landfill in the 19th century. This new land became a hub for Irish, Jewish, Italian, Lebanese, and Chinese immigrants. Over time, more Chinese immigrants settled in the neighborhood. New residents opened businesses that would have reminded their neighbors of their home country. Laundries, restaurants, grocery stores, barbershops, garment shops, and other businesses flourished. Starting at the turn of the 20th century, more and more families settled in Chinatown. They found support in civic associations, schools, places of worship, and youth programs.

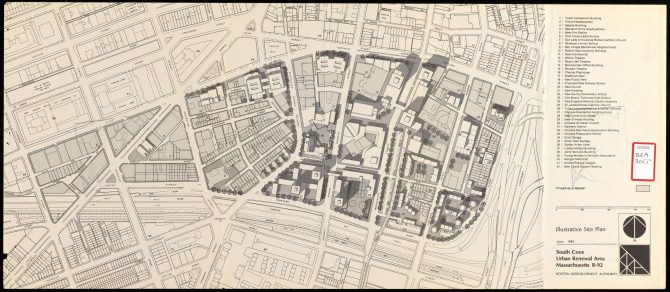

Chinatown became the cultural, social, political, and institutional heart of New England’s Asian American communities. But majority-immigrant communities became targets for large-scale urban renewal projects around the country. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (the predecessor of today's Boston Planning and Development Agency) seized land through eminent domain. These parcels were then sold to developers or institutions, or paved for highway extension projects. This urban renewal process displaced thousands of people in Boston's Chinatown, West End, and South End neighborhoods.

Throughout Chinatown’s history, residents fought to defend their community. Individuals and organizations demonstrated their political power through grassroots organizing and coalition building. These coalitions included activist groups, social service agencies, faith organizations, social and cultural associations, and political organizations.

One well-documented example is the story of Parcel C, a small plot of land in the center of residential Chinatown. Tufts-New England Medical Center planned to build a multi-story parking garage on this parcel. This would have placed traffic and exhaust fumes just feet away from the neighborhood's only public daycare. Neighborhood residents and organizations formed the Coalition to Protect Parcel C for Chinatown. Through years of organizing and networking, the Coalition halted construction of the garage. For a deeper look into this history, check out Michael Liu's new book, Forever Struggle.

Bringing History Together

Chinatown remains home to many of these same community members and organizations that continue to fight for residents’ rights. These individuals and organizations maintain records that tell a piece of neighborhood history. These records may take the form of:

- brochures

- flyers

- posters

- photographs

- letters

- internal memos

- meeting reports and minutes

- recorded interviews

- films

- maps

- architectural plans

- neighborhood directories

- newsletters

- and other materials

To researchers, these records are primary sources. A primary source is an original document or artifact, created by people who experienced an event firsthand. These materials provide vital historical evidence for researchers. They offer clues about the deeper stories behind an event or movement.

Many area libraries, archives, and museums also hold collections about Chinatown’s history. Some of these collections are well documented and digitized, making it easy for researchers to access them. But many more have yet to be catalogued, making them difficult to locate. And with records spread across so many places, it can be difficult to know where and how to begin a research project.

Here’s where the Boston Research Center (BRC) comes in. The BRC is a digital archives and community history lab that works to tell Boston’s deep neighborhood histories. It is a joint project of the Northeastern University Library and the BPL, generously funded by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. In partnership with several community organizations, the BRC launched a survey to inventory Chinatown's historical collections. Powered by community feedback, this survey will help us identify historical collections and community history projects that tell the stories of Chinatown. We can use this information to support ongoing community projects. We can also identify items that need preservation or digitization support. And finally, we can create a searchable database to help researchers navigate these collections.

We worked with our community partners to develop this survey in Chinese and English. Do you know of collections or projects that we should consider? We invite you to respond to this survey using the links below. You can also email us at brc@northeastern.edu.

Collections survey: simplified Chinese

Collections survey: traditional Chinese

This project was designed with the following individuals and organizations, without whom none of this would be possible:

- Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center

- Pao Arts Center

- Chinese Historical Society of New England

- Chinatown Community Land Trust

- Chinatown Branch of the Boston Public Library

- Friends of the Chinatown Library

- Dr. Michael Liu

Learn More

Alex Krieger and David Cobb, eds., Mapping Boston, opens a new window, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

Boston College Department of History, Global Boston, opens a new window, 2021.

Boston Redevelopment Authority, Diagnostic Report of Residents to be Relocated—South Cove Urbal Renewal Project, opens a new window, Boston, 1967.

Michael Liu, Forever Struggle: Activism, Identity, & Survival in Boston’s Chinatown, 1880-2018, opens a new window, Amherst: University of Boston Press, 2020).

Add a comment to: Bringing History Together: A Chinatown Collections Survey Project