Like any city, Boston can sometimes seem like a place apart from nature, a place where humans live to the exclusion of other living things. But this is not and never has been entirely true.

What I hope to explore is how we can think of Boston not just as a dense collection of people and buildings but as a unique kind of habitat, shaped over time by a shifting variety of human and nonhuman life.

By understanding the life that shares the city with us, how it has changed over time, and how past residents of Boston have thought about, studied, and managed the city as a natural space, we will be better equipped to make choices that will allow Boston to thrive as a place not only for people but for many kinds of living things.

Land and Water, Plants and Animals

To see the city as an evolving natural place, it helps to understand what was here before. Indigenous people have lived in this area for millennia, and fish traps were built in the waters below what is now Back Bay about four thousand years ago. But their settlements and lifeways affected the land and its other living residents less than Europeans later did, and the history of Boston as the city we know begins in the 1600s.

Just before Boston was founded in 1630, the area of what is now downtown was called Shawmut and was home to a single Englishman, William Blackstone (or Blaxton). It was a peninsula, connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land called the neck.

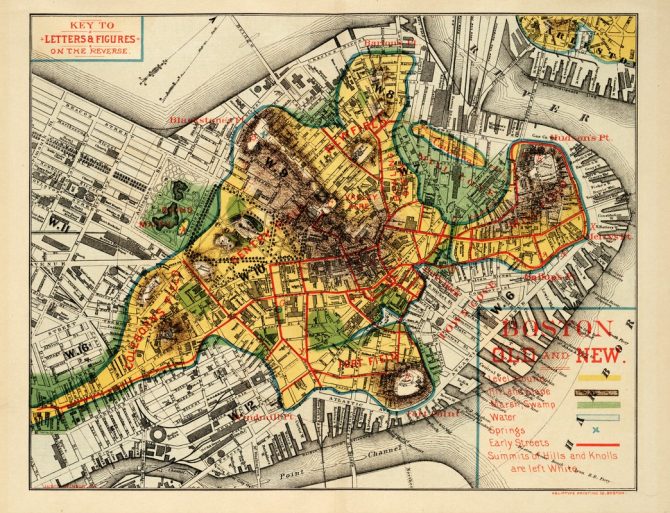

But what was it like? What would you have seen had you walked around Boston before it was Boston? Anne Pollard, who had been among the first English settlers in 1630, later recalled that the land was “very uneven, abounding in small hollows and swamps, covered with blueberries and other bushes.” The map below gives a good sense of what the land was like around 1630 (click the image for a larger view).

, opens a new window

, opens a new window , opens a new window

, opens a new windowWilliam Wood, who visited Boston in 1634, commented that the absence of woods and meadows spared the first residents of Boston from the “three great annoyances, of Woolves, Rattle-snakes, and Musketoes.”

There were rattlesnakes nearby, though; John Josselyn, who visited the area in 1638, saw one in Charlestown “as thick in the middle as the small of a man’s leg."

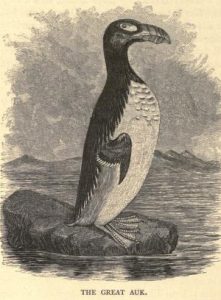

While a few timber rattlesnakes still live near Boston in the Blue Hills, many of the other creatures that early visitors saw are now gone. Great auks (now extinct) swam in Massachusetts Bay, wolves and mountain lions roamed the surrounding woods, and overhead flew millions of passenger pigeons, in flocks “so thick,” wrote Josselyn, “that I could see no Sun.” In the Charles River, huge beds of foot-long oysters prevented larger ships from sailing upstream.

Learning More

These and other remarkable descriptions of the natural life of the area that became Boston can be found in materials in the Boston Public Library's collections. Check them out or read them online to learn more about the life of Boston before it was Boston.

New England's Prospect by William Wood

William Wood wrote one of the earliest descriptions of Boston after its founding, and published his account in 1634. Our Rare Books Department has a copy of the original edition, opens a new window, but a 1764 reprint, opens a new window can be read through 18th Century Collections Online and readable reprints from other libraries can be found on the Internet Archive. Read his descriptions of the area's plants and animals in Chapters V-IX, opens a new window, and his description of Boston and other early towns in Chapter X, opens a new window.

An Account of Two Voyages to New-England by John Josselyn

John Josselyn's description of the area, including his rattlesnake encounter in Charlestown, was published in 1674. Check out this reprint from the Central Library, opens a new window or read this copy from the Internet Archive, opens a new window to see how he described the natural life of New England.

The New English Canaan by Thomas Morton

Thomas Morton lived in what is now Quincy, and published The New English Canaan in 1637. One of the BPL's copies can be read online through the Internet Archive, opens a new window. See the 'Second Booke', opens a new window for his descriptions of the area's plants and animals.

The Memorial History of Boston, Volume I, edited by Justin Winsor

The first volume of this 1880 history of Boston, edited by a former trustee and superintendent of the BPL, covers the 'Early and Colonial Periods' and includes chapters on the plants and animals that lived in the area, as well as descriptions of the land and natural features when the city was founded. You can read a copy in the library, opens a new window or see a digitized version on the Internet Archive, opens a new window.

Add a comment to: Boston’s Flora and Fauna in the 1630s